Our Stories

We acknowledge the legacy of the Traditional Owners of this land, their ancestors and descendants, Elders past and present and their rightful inheritance to the country they occupied for thousands of years. Ancestors are mentioned in the stories below only in the spirit of recognition of the battles and tribulations they had to endure, these matters have not been resolved and will never be forgotten.

Keepers of the Sacred Place - The Goombri

"Long ago 'kaboon' water... from mountain to mountain, all blackfellows go to Terry hai hai (there is high land there) at first plenty kangaroo, opossum, and other food—(they too had taken refuge on the high land)—then when these failed, blackfellow catch fish and live until land dry again—happened long ago—father and father and father tell it long, long, long ago." As told by an unknown muri at 'Yaggabi', c. 1838.

The traditional people of the Terry Hie Hie district, situated between Mt Kaputar and the Gwydir River in New South Wales, were a large clan-group and a dominating influence in the wider region. With a mountain range running through the middle, their country was bountiful and varied, a refuge area in times of big flood. The name Terry Hie Hie is thought to be derived from the Gamilaraay term for 'refuge' or 'high ground', dhirrin. They kept the law of their country strong and led the fight against the colonists in the Gwydir region, ultimately at great cost.

Their activities are mentioned by Ion Idriess in his book Red Chief, he talks of the hero of the story ‘Red Kangaroo’ and his hatred of this tribe from the north who conducted raids into his country on many occasions:

“(Red Kangaroo was) … itching to get within spear-throw of those lean, muscular blacks stealthily moving ahead. Coombri men from Terri-Hi Hi by their tribal scars and war-paint – noted women stealers…” 1

Tribes were sometimes compelled to find additional women for partners, though not all were taken against their wishes, this was a practice most tribes undertook. But importantly, Terry Hie Hie was a regionally significant gathering point for tribes during annual bora (buura) ceremonies, the burra ground was thought to be one of the largest recorded in New South Wales. Noted by Dr John Frazer in 1882 in his article, 'The Aborigines of New South Wales', he says, "The great ancestral Bora ground of the Kamilaroi tribe is at Terry-hie-hie."2 A detailed description of the ceremonial grounds and location was provided by R. H. Mathews who visited the site in 1901, of two different, adjoining circles, a larger one for gatherings of the whole tribe and visitors and one just for the initiation of young men.3

The first colonists seen by the Goombri people were probably a result of escaping convicts and the activities of bushrangers. Following the settlement of the Hunter Valley and Bathurst area, many convicts it seems took their chance in the wilds of the countryside, often ending up many miles past the limits of the colony, though few survived. One who did well for himself was George Clarke who escaped from convict service in 1825 and fled by all accounts to the lands of the Gamilaraay. According to Dean Boyce,4 Clarke, "... was recognised by them as ghost of a dead tribesman", and that he had "... Aboriginal wives, cicatrization, possum skin cloak, grass bead necklace, hair belt." Clarke stated he obtained his initiation rites at the Terry Hie Hie buura ground, where the "... greatest boras were always held..."

The Surveyor-General of New South Wales, Sir Thomas Mitchell was the next to travel into Goombri territory in January of 1832 and he encountered different individuals and families going about their daily business. Most kept their distance, wary of the train of horses and bullock-drawn carts, which would have been a new sight to behold for the majority. When contact between the cultures was attempted by the tribal people, Mitchell’s distrust prevented him attending their camps in a sign of mutual respect. Out of frustration one group threw together an in promptu dance ceremony for Mitchell, but no relationship was established. Distrust was fostered and resulted in the homicide of two of Mitchell’s supply party at ‘Gorolie Ponds’, on the western side of Goombri country, the reasons why the men were killed is not clear now. Mitchell was gripped with fear for his safety and made his way quickly out of this country, though was followed all the way:

“The natives there were not unlikely to be formidable enemies, encouraged by their late success; and, with such prospects before us, it was by no means agreeable to be thus followed in rear by others.” 5

On his return, Mitchell, notwithstanding his troubles with the originals, provided glowing reports on the suitability of the country for pastoralism and the movement of cattle down the Horton and Gwydir Rivers was underway by 1833. In no time runs had been set up all the way down the Big River to the current location of Moree. The first stock runs were usually taken up by managers with their few stockmen, the owners were generally based in Sydney and the Hunter, seeking to expand their family empires sometimes appointing their sons as managers. The stockmen were often serving and ex-convicts or adventurous young, immigrant men seeking opportunity. Charles Naseby was a station manager on one of the first runs set up on the Gwydir, 'beyond the limits', at 'Yaggabi'. He records the squatters and herds were 'flowing across the Liverpool Plains' in a west ward flood of land-grabbers, lamenting that the authorities had little real control on what was happening on the frontier.6

Runs were unfenced and stock had to be tended closely by their handlers to guard against them wandering. Isolated stockmen were easy targets for tribal people who wished to defend their lands, as were the stock themselves. It was the animals that were doing the damage to country, fouling the water points and driving away the native food animals which caused the greatest resentment by the tribal people, who in turn came to regard the new cattle as fair game. Naseby records the deaths of four stockmen somewhere in the Gwydir district in 1834, possibly the first white deaths in the region recorded since the killing of Mitchell's supply party.7 The details are now lacking, though it seems these deaths fit the pattern of being in the wrong place at the wrong time, ignorant of the ways of the tribal people, making the supreme sacrifice for distant masters.

Being greatly outnumbered, some of the newcomers found it expedient to get along with the tribal people as best they could, Naseby records how he later gained trust of the local tribe, learning their language and showing courtesy to their presence. Naseby allowed the use of his lands by the tribe he encountered at 'Yaggabi' and valued their knowledge. He identified two ‘chiefs’ or tribal elders who would come to visit him, ‘Bullinkodjie’ and ‘Yabbawnba’ which means "great talker"8. As this section of the Gwydir is closet to Terry Hie Hie, it is likely these people were a clan of the Goombri.

The traditional owners it seems attempted to tolerate the presence on their country of small holdings of stock, their message system told them that these were just a few of the whitemen and that many more may come and so tried to keep a peace. It was reported often how tribal people would act as guides, even finding water and food for the whitemen. But in 1836 this peace was broken. Two stockmen were killed by the clan of Terry Hie Hie Creek following their failed raid on a camp to kidnap tribal women. These men were from a run taken up by George Bowman, which he called ‘Terry Hie Hie’ covering over 200,000 acres. This was followed by the killing of a convict who was assisting the son of the squatter Hall to set up a run on the Mehi River, following a trail of bad behaviour and misunderstanding.

Sketch from, Sir Thomas Mitchell. Journal of An Exploring Expedition To The Interior Of New South Wales Through The Liverpool Plain, 29 November 1831-16 February 1832. (Vol. 2), 1838.

By 1836, the numbers of colonisers on country had increased and following the killing at Hall’s claim, the first organised retaliation by the newcomers was recorded, a posse set out killing anyone in their way, resulting in the death of some 80 tribal people, exactly where is unclear, probably somewhere near the Hall's run 'Wee-bolla-bolla'.9 This was followed the next year by a massacre of hundreds of people near Mt Gravesend in two separate incidents.10 Mt Gravesend sits just south of the Gwydir River, with the Goombri people to the south and the Wallaroi people to the north. Both tribes may have suffered in these incidents near the runs of the squatters Cobb and Bell whose men were largely responsible for these atrocities.

But more was to come the following year, in a series of unprovoked callous massacres. In January 1838, some 200+ people were killed at a large inter-tribal gathering (about 1,000 people in attendance) on a lagoon on the western Gwydir floodplain, at a place which became known as ‘Waterloo Creek’.11 This was undertaken by an official force of 30 armed Mounted Police led by Major James Winniett Nunn, with 20 other hired guns from the various stations. This was the country of the Native Orange people, the Yulnaalumbil, though Goombri and perhaps other tribes were also present. It was a surprise attack in country that no squatter had taken up at that point.

Five months later, another massacre occurred through deception, with stockmen feigning a willingness to share their stock with the originals. This occurred on Slaughterhouse Creek to a clan of the Goombri, as recalled by a descendant, George Jenkins:

"My mother used to talk about Slaughterhouse Creek thing. They went to all the dark people, called them in, killing a bullock. Them all come in get some meat. When they all come in they just, told 'em to come into the yard and shot 'em down and knocked the kids in the head they say. I don't know why." 12

Goombri family history recalls some 140 deaths in this incident, though there were some survivors, who lived to tell the tale.13 Some of the stockmen involved in this atrocity went on to kill the unarmed women and children who were the Wiriyaraay families of workers on Myall Creek Station a few weeks later.14

This was the last straw for the Goombri. In a year, at least two clans had been nearly destroyed for no good reason, their view became, as their actions were to show, that there could be no peace with the whitemen. They devised a strategy to remove all stock from their country and anyone who got in their way and were the first of the Gwydir tribes to retaliate, in the same month as the Slaughterhouse Creek massacre. This retaliation had a decisive impact on the squatters around Terry Hie Hie:

"May, 1838 :— I brought away all the cattle and sheep, and everything else of any value. I was very sorry to be obliged to leave my station, but it would have been certain death to remain with eight men and one musket, and no hut up. Faithful and Bowman (of Terrie Hie Hie) have left their cattle running about wild, and Colonel White buried his property in a hole dug in the ground—they fled and left me alone after advising me to leave every-thing and fly too. I brought everything away, even to a calf which a cow had dropped the very night before”.15

It was a clear sign by the original owners of this country to the colonists that this was their land and they would defend it. The attacks on stock spread. In a short time, by November of 1838 in fact, most of the lower and central sections of the Gwydir and most of the Mehi River had been de-stocked due to the ongoing raids by the Gwydir tribes, as this letter to the editor of the Sydney Herald stated:

"The Blacks have commenced in earnest. On 27th of October they visited the Runs of the undermentioned individuals, whose stations are on, and in the vicinity of a place called the Island (Ardgowan), Fitzgerald, Marshall, Pitt, Inch and Hall, and drove off the whole of their respective herds, amounting altogether to about three thousand head of cattle. They drove them in a westerly direction. On the following day a party of five persons followed them and have not since been heard of; great fears are entertained that these knowing savages have sacrificed them to their fury.” 16

In response to this, the government despatched their newly appointed Crown Commissioner of Lands and Protector of Aborigines to the Gwydir, Edward Mayne, who arrived in January 1839 to try and bring peace to the region. He was the first government official to attempt discourse with the tribes and while he was there made assurances to them that they would be allowed to go about their business, free from harassment. He even sent out a directive to the stations banning the carrying of guns. When he travelled down Terry Hie Hie Creek he noticed some of the runs still abandoned from the previous year's troubles. However, after three months, Mayne departed and violence quickly flared again. The tribes waited for his return, but it never came, nor did any recognition from Sydney of the work he had commenced.

Angry at this betrayal, the tribal people's strategy to drive off the cattle from the river had resumed by mid-1839, as this report from ‘Biniguy’ station on Goombri country details:

"Since that we have brought in three cows and taken spears out of each of them, and I have no doubt many more of yours are killed and taken away, but cannot give you a return till we muster which will be some time as they have scattered them in every direction ; and if the blacks go on as they are now doing, it will be perfectly useless to muster, for as fast as we collect them on the run they drive them off. I sincerely hope we shall soon have some sort of protection from the Government, if we do not, I know not what the consequence will be, as the blacks are much worse down the river than they have been yet, and I expect daily to hear of more white men being killed by them, as they are threatening every station and every white man on the River." 17

The conflict raged on for a year but by 1841 had died down somewhat, in part due to the lack of stock left in the region, in part due to retaliations from some of the squatters including the use of poisons and incursions by police to apprehend offenders. But things took a turn for the worse again for the squatters in August of 1842, when a large inter-tribal gathering was held at the Terry Hie Hie buura ground.18 The Terry Hie Hie runs had to be abandoned again as an orgy of cattle killing began in earnest. The men had devised heavy spears built specially for the purpose, often only the tongues or fat of the cattle were taken, the carcasses left to rot.

Whatever was discussed at the gathering of warriors, following the buura at Terry Hie Hie, the attacks on stock and station again escalated as the squatters attempted to restock the runs. Between 1842-44, it appeared that a concerted and co-ordinated outbreak of war had been declared on the frontier by the Aboriginal peoples in what was called by the squatters as 'The Rising'. This period of cattle displacement, though not well documented, appears to be a period of heavy conflict on the Gwydir and in the view of the squatters, was "... the result of a perfect organisation, effected with all the aids of negotiation, secret intrigue, and general assemblies." 19

Again, the fightback commenced in Goombri country and by early 1843, the situation had become very bad for the squatters and their stock throughout the Big River. By what accounts are preserved, most runs by April had again been abandoned:

"The destruction on the Big River has been immense and is still going on. No description of property is safe; they appear to kill for amusement. They commit murder without interruption. It is only within this three weeks that two policemen have made their appearance. Around Mr. Fitzgerald's lower station ('Midkin') the country becomes very swampy, and there are large beds of sage, which from the late rains have grown so tall and rapidly as to afford shelter to the blacks. No horseman can approach them, and the policemen and party were not courageous enough to charge them on foot. How long are such unpardonable outrages to be winked at by government or do they, like the blacks, find amusement in the destruction of the property of the settlers and the lives of their men? As we now stand, we are sacrificed to the savages. Upon what grounds such a measure can be justified, I plead my ignorance. Unless the blacks receive an immediate check, it will soon be impossible to retain our position on this river." 20

We don’t know the extent of loss of life during this period, the events which took place and incidents that occurred seem to have been subject to a public and official silence. Police could make only a relatively low number of arrests compared to offences, it is safe to say that they were completely overwhelmed and most retaliatory 'justice' metered out by the colonists simply went unreported. While it is not clear as to the extent of loss of life, accounts describing 50 people having been killed on the Barwon River in six months suggest that many unrecorded colonist and tribal lives were lost between 1842 and 1845.21 'The Rising' had succeeded in de-stocking large areas of country in the Gwydir again for the third time. But like previous attempts, it was a temporary gain for the tribal people as more settlers, workers and stock eventually moved in to take up the runs and pastoral expansion in the region continued, as did the violence and dispossession. While the colonists kept coming, the losses for the tribal people were mounting and could not quickly be replaced. It was a war of attrition, which ultimately the tribal people could not win.

The remaining Goombri people and those throughout the Gwydir region were faced with some stark choices. To be one of the 'wild blacks', to keep away from the whitemen and take refuge where you could, often on marginal or off-country locations, or to accept assistance from the colonists, those that were inclined to show the original owners some compassion and respect and allow co-habitation to occur. No doubt many of the squatters were grateful for the help they had received from the tribal people setting up their runs and valued their assistance. Luckily for them some of the landowners of the Terry Hie Hie district fell into this category, the tribal people were quick to work out who they could trust and who they couldn’t.

The 1850s saw a period of growing use of Aboriginals as farm workers as relationships with landowners were forged and more cooperative land and labour arrangements became standard practice. There was a lack of white labour on the frontiers at this time made worse by the gold rushes and Aboriginal men and women proved themselves to be very useful stock handlers, though a proportion of the Aboriginal population was often kept hungry. Losses in the indigenous population though by 1850 is thought to be of the order of magnitude of 90% from their original size and it is not clear how many of the Goombri had survived on country by this stage. Despite their reliance on black labour, mention of Aboriginal people in correspondence was not common and only where English names were used. One account from 1855 identifies the tribal ‘chief’ of Terry Hie Hie taking the surname ‘Boney’ with a daughter known as 'Kitty', other names used for Aboriginal people in the region include Maria, Sally, Sarah, Billy and Jacky.22

The 1860 and 70s saw consolidation of station camps for aboriginal workers but also the emergence of unofficial or ‘free camps’ on many of the crown lands which had been resumed by the Government for the protection of water sources. Many of these were on culturally significant areas, such as the upstream pools of 'Two Eyes' Mil Bullen at Mt Waa, a reference to the Great Serpent of the Dreaming. While many now were reliant on rations and handouts from the station owners, traditional foods and water sources were still widely sought after. Terry Hie Hie was a good location for this, due to its varied landscapes and resources, from mountains, to streams and grasslands. One notable Goombri man known as Cobraball took to the life of bushranging, and remained elusive with his stash of gold for a considerable time in 1850s and 60s, hiding in the hills.23 An observer who went to Terry Hie Hie station in 1873 reported a “good many Aboriginals” present there, no doubt both on station and free camps.24

As before colonisation, surviving Aboriginal people from different parts of the region came to Terry Hie Hie - attracted by good working and living conditions as well their cultural and kinship ties. Some names have been recorded in the Moree and District Court House Death Records25 which identify families from the upper Gwydir, Namoi and MacIntyre as well as Goombri survivors. The area also became a melting pot of black survivors and white labourers, usually with white men taking black wives, but also black men partnering with mix-blood women. Many of the ex-convicts or children of convicts who settled on the stations, whether they were long or short-term workers, provided a legacy from this period which remains with the Aboriginal community today.

Court House Death Records and other sources identify approximately 11-12 people who it is thought are of the original Goombri people and old enough to remember the early contact period. These include Marie Brummy and partner, Brummy, who were recognised by the squatters as 'King' and 'Queen' of Terry Hie Hie in the 1870s, Kitty Timmins (Boney?), Sally Poppit (Nerang), John Poffit (Tippo), Cobraball, ‘Frying-pan’, Peter Cutmore, Mary Mag, Louisa Drumming and Billy Barlow. These are records for the most part taken from known burial sites, though it is known that burials were still being conducted in secret, away from the eyes of the authorities into the 1900s.26

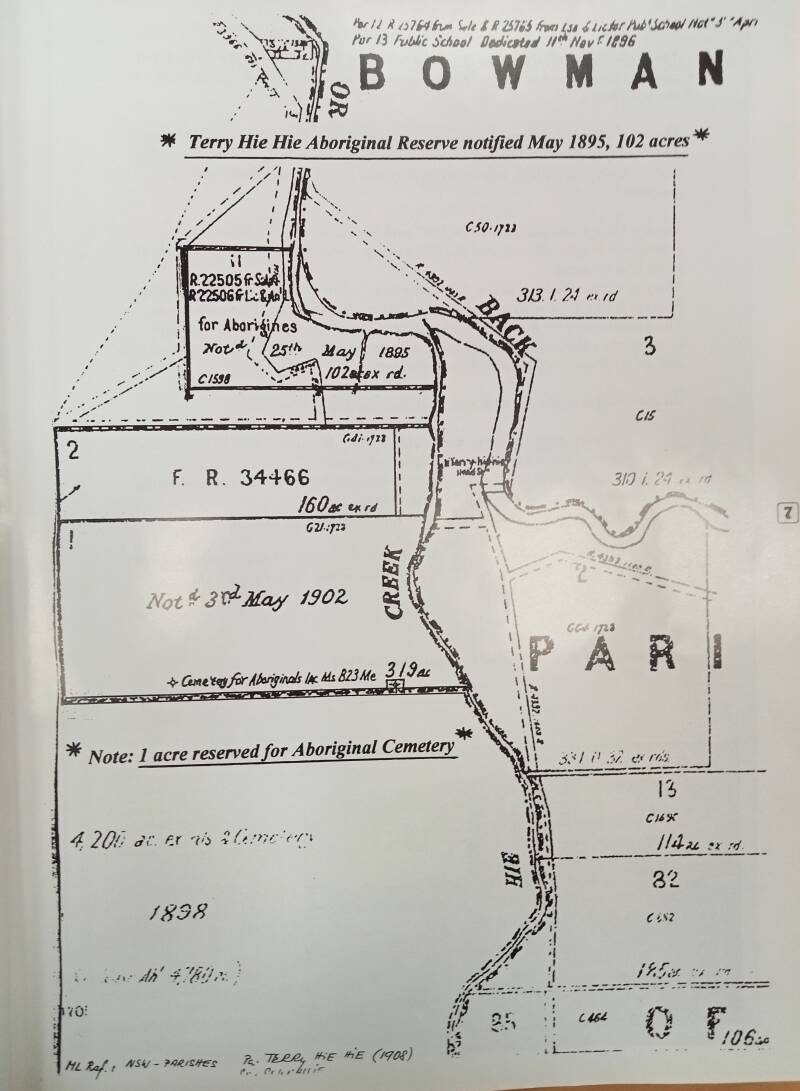

The Aboriginal Protection Board set up a reserve in 1895 to provide rations and educate Aboriginal children. It was located north of the old 'Terry Hie Hie' run, though it took a good many years before any of the locals who were living at various camps made the move to the reserve itself. But due to the child removal activities of the Board, the 1917-1922 period saw an exodus of Aboriginal families from Terry Hie Hie. They went to other reserves and camps across the region, notably ‘Top Camp’ near the town of Moree, first established as a free camp by Peter Cutmore and his family late in 1917.

Government sketch of Aboriginal areas reserved at Terry Hie Hie in 1895.

References

- Idriess, Ion. Red Chief. Angus and Robertson, 1953, 226 pages.

- Dr John Frazer, ‘The Aborigines of New South Wales’, Royal Society of New South Wales, 1882, Vol. xvi, p. 216.

- Description of Two Bora Grounds of the Kamilaroi Tribe. The Terry-hie-hie Bora Ground. By E. H. Mathews, l.s. 423, Royal Society of New South Wales, 1917. Sydney C. Potter, Acting. Govt. Printer.

- Dean Boyce, 2013. ‘Clarke of the Kindur: convict, bushranger, explorer’. Melbourne University Publishing. 118 pp

- Sir Thomas Mitchell. ‘Journal of An Exploring Expedition To The Interior Of New South Wales. Through The Liverpool Plain’. 29 November 1831-16 February 1832. (Vol. 1), 1838. p. 93

- Testimonial of Charles Naseby, Reported by John Frazer in the Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, Saturday 24 December 1881.

- Testimonial of Charles Naseby, Loc cit.

- Testimonial of Charles Naseby, Loc cit.

- Threlkeld, Lancelot, 7th Annual Report to Colonial Secretary Thomson, 20.6.1837, in ‘Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L. E. Threlkeld Missionary to the Aborigines 1824-1859’ (ed. N. Gunson), Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1974; Mahaffey, Kath. 1980. Pioneers of the North West Plains. Moree and District Historical Society. p. 98.

- Edward Mayne, Evidence to LC Committee on Police and Gaols 19.6.1839, p 25, V&P

- Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1919), Saturday 28 February 1874, page 17. Story recounted by the reporter was that it was local common knowledge that near Gurley Station, "... the slaughter of a large number of blacks (the greater part of the tribe) by Major Num (sic) and party," had occurred. The journalist reported, 'There is now living but one blackfellow who escaped that dreadful slaughter. He is called Peter; I had a conversation with him at Terry Hie Hie”; Major Winniett Nunn, Deposition at Merton Inquiry 4.4.1839 HRA, XX, p 251; Nunn, Report of 5.3.1838.

- Testimony of George Jenkins. David McDougall and Bob Reece, 1976. Audio recording held by AIATSIS. ‘MACDOUGALL_D01-006285’ (Moree, NSW 13-14/01/1976).

- "He (Peter Cutmore) said there were about 140 killed ... The woman that got away. She ah, was she was born and bred at Terrie Hie, they reared her up and of course, she was a fair age, I could remember.... but she was only about eight or nine when she crawled through the thickets ... she must have talked to my grandfather and the older people ..." Testimony of Phyllis Suey. David McDougall and Bob Reece, 1976. Audio recording held by AIATSIS. ‘MACDOUGALL_D01-006283’ (Moree, NSW 13/01/1976).

- Testimony of Len Payne. David McDougall and Bob Reece, 1976. Audio recording held by AIATSIS. ‘MACDOUGALL_D01-006281’ (Moree, NSW 11/01/1976).

- Sydney Herald, Thursday 7 June 1838, page 3

- A Grazier. Hunter's River. Sydney Herald, Monday 26 November 1838, page 2

- ‘A Sojourner In The Wilderness’. Sydney Herald, Wednesday 16 October 1839, page 2

- Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), Thursday 27 October 1842, page 3

- The Aborigines of Australia. No. XIV. The ‘Rising’ of 1842-4. Reprinted in ‘The Empire’ (Sydney, NSW : 1850 - 1875), Saturday 15 April 1854, page 4

- Big River. Australasian Chronicle (Sydney, NSW : 1839 - 1843), Thursday 6 April 1843, page 2. (First reported in the Maitland Mercury).

- The Blacks On The Barwon. Maitland Mercury, reprinted in the Sydney Morning Herald, Tuesday 12 September 1843, page 3

- A Warialda Black. Warialda Standard and Northern Districts' Advertiser (NSW : 1900 - 1954) Tuesday 5 December 1905 - Page 2

- Vivid Days at Terry Hie Hie - Black Outlaw - Hidden Gold In Hills. Gilgandra Weekly and Castlereagh, Thursday 30 October 1930, page 1

- Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW: 1870 - 1919), Saturday 21 February 1874, page 20

- Lola Cormie. ‘Moree on the Mehi: Court Death Records 1860-1975.’ ISBN 978-0-9751184-5-0, © 2012. MIE Print, Killarney Vale.

- Testimony of Walter Katon. David McDougall and Bob Reece, 1976. Audio Recording MACDOUGALL_D01-006285. Location/Date: Moree, NSW, 14-01-1976. Held by AIATSIS

The Wallaroi – a people remembered

Australia continues on its journey to place the indigenous heritage of the continent into proper perspective and what that means in our everyday lives today. The story below is an example of how things were brushed under the carpet. It is the forgotten story of massacres and the attempted elimination of a people. It is important now this story be told.

While doing research over the last few years for a book which looks at the early post-contact period for an area of New South Wales (the Gwydir River), an account of events we had never heard of before came to our attention. It was the story of a people, or a tribe, who had existed on their country for millennia, and the devastating truth about what happened to them.

Researching our contact history can be an ordeal as many of the records do not exist in the archives today – for one reason or another, though stories of our past can still be found now, buried in collections of local museums and historical societies. One such document was located within the records of the Warialda Historic Society last year and is titled the 'Early History of the Warialda District', transcribed and presented to the Society by the daughter of a Mr Basil E. Moor.1 The account contains very detailed descriptions of indigenous story and knowledge, told to the author by, “an old Aboriginal who worked for my father at various times in my youth … he informed me he was the last of the initiated Kamillaroi and had been entrusted with the secrets of his race,” as well as other local settler story from the Warialda district. The only date provided is the timing of the events in the story, said to have taken place in the spring of 1846.

1846 was some 13 years after the first squatters drove their cattle down the Gwydir River, some of the massacres and conflict along this stretch of country have been documented, particularly during the 1836-38 period. The First People of the Gwydir country, according to all sources, were a collection of different tribal groups and languages. The focus of the story presented by Moor are a traditional group of people who were called the ‘Wallaroi’ and lived within an area on the northern side of the Gwydir, around where the town of Warialda is today. This people are also mentioned in another account which uses an indigenous source, Red Chief, written by prolific author, Ion Idriess, who identifies the 'Walleri' as a tribe of the Gwydir region2.

The first time this people are mentioned in official records is from the correspondence of Commissioner Edward Mayne who ventured into the troubled Gwydir district in early 1839 on his failed attempt to bring peace in the region. Following the massacres, the colonials found themselves under siege by a strategy adopted by the original people to remove all stock and their human handlers from the region altogether. Mayne’s mission however came unstuck as he found himself without support from the squatters or the government in Sydney because of his alleged pro-aboriginal bias. The conflict and loss of life raged on for at least six years, but peace did reign on the Gwydir for about 3 months, while Mayne was there.

During this time Mayne visited the different tribal groups along the river, though he did not name them, one group was near the stock run of a Reverend David MacKenzie who had set up on a stream called Reedy Creek, which is Warialda Creek today. Here he was co-existing peacefully with a ‘friendly tribe’ and Mayne travelled to meet them in January of 18393. While most kept to themselves away from the squatters, some had come in to assist the Reverend with his pastoral duties and perhaps to learn the ways of the intruders. One boy, probably in his young teens, could speak English and made himself understood, such that Mayne gained considerable intelligence about the activities of the squatters and their war with the tribes.

The boy told Mayne that his tribe wanted peace with the newcomers, as they had been greatly affected by the actions of the local squatters. The tribes down the river however, according to the boy, were the “Never Never tribe” in that they would not stop killing cattle or fighting for their country. Mayne tried to enlist the support of this people to accompany him on his mission to bring peace to the region by acting as guides and ambassadors for him, but his offer was turned down4. But the tribe preferred to stay out of this business and gave him the strong impression of their peaceful nature and desire to be left alone.

This concurs with Moor’s story of the Wallaroi. Traditional knowledge held by his Gamilaraay-speaking source described them as the 'old people', being the first inhabitants of the region 'since the Dreamtime'. This source stated that the ‘Kamillaroi’ arrived some 500 generations ago from the north, being a more aggressive culture, who allowed the Wallaroi to live in their country with the understanding they attend annual war games and ceremony. These meetings had been occurring ever since.

One important cultural site where the ‘war-games’ were held was somewhere along a northerly flowing creek, now called Ottley Creek, which flows past the mountainous feature of ‘Blue Nobby’, some 20-30 km north of Warialda. The narrative states that this area was also used for male initiation ceremonies by the Wallaroi people.

The narrative states that the Wallaroi spoke an ancient dialect, known as 'Yuwalyai'. Thanks to the linguistic work undertaken on these languages5, today we know this as the Yuwaalaraay dialect, generally thought to be spoken west of Barwon River but there is considerable historic evidence from observers in the 19th century that it was also a language of the Gwydir River6. The term ‘Wallaroi’ comes from the name of their language, early observers place it as a language spoken north of the Gwydir River, with Gamilaraay spoken to the south of the river7. The first government official in the area, Commissioner Richard Bligh, referred to them as the Ginabaa, possibly a term they used to describe themselves. Another dialect, Wiriyaraay, was spoken along the MacIntyre River, to the east and north of the Wallaroi 8.

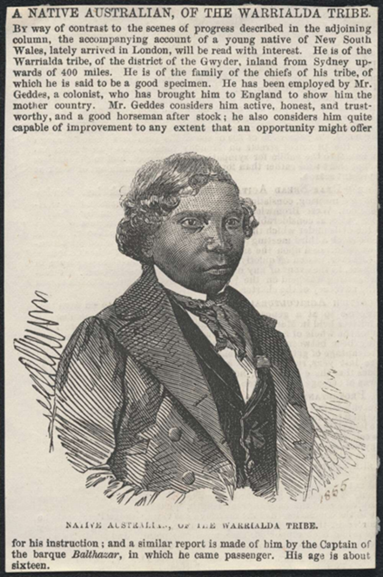

“A native Australian of the Warrialda tribe”. 1855. Picture held by National Library of Australia (nla.obj-135902925)

While fighting was going on along the Gwydir and MacIntyre Rivers between 1839-1845, the Wallaroi country lay in between them, they endeavoured to remain peaceful. And to some extent they were able to maintain their traditional lifestyle into the early 1840s, however the events of 1846 changed everything for them. At this time, the MacIntyre tribes were on the war-path, with many runs lying abandoned for years, the stock losses were so high. Like what happened on the Gwydir, the MacIntyre tribes would drive the cattle off the runs to remote locations to slaughter or keep the animals for a while. All stockmen were at risk, as the Wiriyaraay people were regarded as formidable opponents and many deaths of stockmen had occurred. 9

Policing at this point was sporadic as teams of Mounted Police had to be despatched on expeditions, generally from the Hunter, to undertake any policing actions. The only official presence in the Gwydir/MacIntyre region at the time was the newly appointed Commissioner, Richard Bligh who had set up his office in a tent on Reedy Creek in 1845. But there was no other force stationed in the region to assist him, the first officers were appointed to Bligh in 1847.

The Ottley Creek meetings of warriors of the different tribes was still occurring during the 1840s and local settler story tells how they were getting angry and vengeful because they could not use all the land assigned to them by the authorities. It is thought that the annual gatherings were taking place near or on a run called ‘Yallaroi’ near the MacIntyre town of Coolatai, owned by the squatter, Marks, who went on to commit further atrocities in the following years. All the squatters and their men had to keep their distance from the 100s of armed warriors which would gather here each year. In conjunction with the Mounted Police, it seems, they planned an ambush for them.

So, in 1846, a police force of unknown size was sent to quell the ‘aggressive natives’ on the MacIntyre, this force had brought with them some ‘field guns’ probably light artillery pieces that could be dismantled for easy transport. Unknown to the originals, they set themselves up to ambush the tribal people while attending their ceremonial field. The victims in this ambush were described as warriors of the ' Wallaroi ' and the 'Kamillaroi'. Mention is made of the 'Native Police' in the account below, though officially there were no Native Police in the region until 1849:

"... the settlers along the Macintyre were getting fed up with the whole thing. Having been unlucky enough to inadvertently found cattle stations on the traditional battle-ground, they found life hazardous and chancy business — particularly in late Spring every year when the place became alive with very unfriendly niggers — which is not surprising because the Kamillaroi were never terribly particular about who they threw spears at any-way. The Native Police were sent for and they arrived with the Border Police in the Spring of 1846 in time to catch the natives lined up for their annual war. The police used light field guns on the assembled Aboriginals and killed over 100 in the initial onslaught. The remaining natives were disposed over the next few days, meaning that very few escaped and certainly none of the Wallaroi." 10

Thus ended a good proportion of the adult male population of the Wallaroi. At the time, their women, children and some of the men were at 'Cranky Rock', identified in the story related by Mr Moor as an important refuge area and cultural place, like many such places, it is associated good shelter with a reliable supply of water.

By the 1840s, the numbers of European settlers in the Gwydir district had increased, and along with Commissioner Bligh had set up the beginnings of a little village on Reedy Creek, probably with a drinking place and store. Unbeknown to them however, the traditional people had maintained their stays at their refuge area as they had always done for millennia. But not long after the massacre at Ottley Creek, maybe a matter of days or weeks, the Wallaroi gathering at Cranky Rock was detected by a passer-by who heard the cries of a child.

The account states that the local colonial people took matters into their own hands because the Mounted Police were away dealing with the natives on the MacIntyre. But how the colonial people responded says a lot about their psychology at the time. It seems their actions were based on fear as the over-riding emotion, no doubt mixed with a racial attitude of superiority, so prevalent in the correspondence of the time. But most disturbing is the idea that a peaceful people, who had lived on their country for 10s of 1000s of years suddenly became a people without human rights or purpose. And so, the cries of a child became interpreted as a sneak attack upon the village. A posse organised and swung into action, the results were dreadful, much more deadly in magnitude than the Myall Creek murders, eight years earlier:

“ … they rounded up the natives in the Cranky Rock area and drove them into a dead-end gully about three miles East of Warialda and proceeded to shoot them over a period of several hours. They didn't take any risks and shot from a great distance - They took their time about it - no one escaped. When they considered the natives were sufficiently subdued, they went in and clubbed the wounded. 123 men, women and children' died in that massacre. It took them two days to drag up enough wood to burn the bodies. I can remember going out there as a child to have a look at the area - you could still see burned earth and scraps of bone and teeth - some people took them home as souvenirs."11

It was at their sanctuary that their old tribal life came to end. Exactly where most of the deaths occurred is not entirely clear, but the creek today still named ‘Murdering Gully’ to the east of Warialda is a likely location. But not all were killed. Records show some stayed in the village as guests of some of the town people, some camped at another location on nearby Mosquito Creek, Commissioner Bligh records about 50 aboriginal people at these locations in 1850 12. Others escaped to another well-known traditional refuge south of the river, at Terry Hie Hie.

The Wallaroi people and their identify seems to have faded over the passage of time. Mention is made of survivors in the early baptismal records of Warialda, individuals were assigned English names like ‘Sussanah’ and ‘Sarah’ and ‘Billy’13. One young man was taken on by the local post-master, William Geddes and educated enough to embark on a trip to the old country, London, in 1855. Here he was received as a celebrity, unlike in his own country, and was acknowledged in the English Press as the, “son of the chief of the Warrialda tribe”14. However, no name was given to this young man in the record and what became of him has not been located, other than a story of his betrothal to the daughter of the neighbouring Terry Hie Hie chief with the name ‘Kitty Boney’.

It is documented that other punitive actions against Gwydir and MacIntyre tribes similar to those outlined here were carried out by the settler community in the 1840s, but not on the scale as these events. If they did occur, additional massacres have so far escaped public attention. Most of the inter-cultural conflicts on the frontier were conducted away from the eyes of the public and a veil of secrecy has descended, particularly in relation to the ending of the conflict on the Gwydir. It is confronting to learn of these events now, some 180 years later. But understanding this history and the reasons why they occurred during the early days of the colony fills a significant gap in our collective understanding.

Many thanks to Silus Telford, who found the original Moor document and kindly made it available.

References

- ‘Early History of the Warialda District’, based on the recollections of Mr Basil E. Moor, transcribed by his sister, Betty M. Moor. Held by the Warialda Historical Society. 4 pages.

- Idriess, Ion. Red Chief. Angus and Robertson, 1953, 226 pages.

- Correspondence of Mayne to Thomson, 6.1.1839, CSR 39/753, Letters from CCLs 1839

- Correspondence of Mayne to Thomson 23-28.2.1839, CSR 39/2519. Letters from CCLs 1839

- Austin, P., 2008. The Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi) language, northern New South Wales – a brief history of research. In McGregor, W. (ed.). Encountering Aboriginal Languages: Studies in the History of Australian Linguistics. Canberra, Pacific Linguistics. Pp. 37–57.

- William Gardner, 1854. Production and Resources of the Northern and Western Divisions of New South Wales, (1854), Volume 1, p 257-258; A. W. Howitt, D.Sc., 1904. Native Tribes of South-East Australia. Macmillan and Co., Limited, New York, London, 1904.

- W. M. Ridley, 1861. Journal of a Missionary Tour Among the Aborigines of the Western Interior of Queensland in the Year 1855 (1861) 439-440 in J.D. Lang, ‘Queensland, Australia’. (Stanford, London; 1861). "... the Kamilaroi is spoken over a wider extent and by a larger number of blacks than any other dialect, at least in that part of the country … At Warialda, and to the East and North, Wolroi is spoken; but just below that town we come on Kamilaroi speaking blacks."

- H. Mathews, 1903. Languages of the Kamilaroi and Other Aboriginal Tribes Of New South Wales. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Jul.- Dec., 1903, Vol. 33, pp. 259-283. Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Early Days in the North-West. Sydney Mail, Wednesday 25 December 1929, page 8. "It is worthy of note that, this is not the first time murders have been committed with impunity on this part of the Macintyre by the blacks. Nearly three years ago they killed two men at the same place, when the station was occupied by Captain Drake; and since then have killed a stockkeeper of Mr. Drake's, named Matt, and speared a stockkeeper of Mr. Huskisson's at the next station."

- ‘Early History of the Warialda District’, Loc. cit.

- ‘Early History of the Warialda District’, Loc. cit.

- Crown Commissioner Richard Bligh. 1851. Annual Report on the condition of the Aborigines of the Guydir District. Historical Records, pp. 18-24.

- J. Mackett, 1989. N.S.W. Birth, Death and Marriages - references to aborigines from 1788 to 1905. Baptismal Records from National Library – Parish of Warialda, 1851-1855.

- A Warialda Black. Warialda Standard and Northern Districts' Advertiser, Tuesday 5 December 1905 - Page 2

Central waterhole at Cranky Rock Nature Reserve. (photo courtesy of Department of Environment and Climate Change)